Chapter 6- Hydrocarbons | class 11th | revision notes chemistry

Hydrocarbons Class 11 Notes Chemistry

Introduction

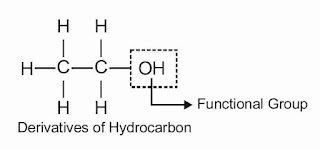

The term ‘hydrocarbon’ is self-explanatory meaning compounds of carbon and hydrogen only. Hydrocarbons hold economic potential in our daily life. Natural gas and petroleum are chief sources of aliphatic hydrocarbons at the present time, and coal is one of the major sources of aromatic hydrocarbons. Petroleum is a dark, viscous mixture of many organic compounds, most of them being hydrocarbons, mainly alkanes, cycloalkanes and aromatic hydrocarbons.

Classification

As we are quite aware that there are different types of hydrocarbons. Depending upon the types of carbon-carbon bonds present, they can be classified into three main categories –

- saturated hydrocarbons

- unsaturated hydrocarbons and

- aromatic hydrocarbons.

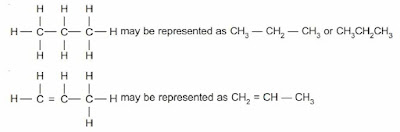

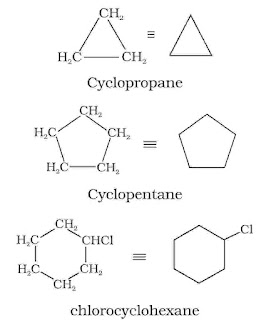

Saturated hydrocarbons contain carbon-carbon and carbon-hydrogen single bonds. If different carbon atoms are joined together to form open chain of carbon atoms with single bonds, they are termed as alkanes. On the other hand, if carbon atoms form a closed chain or ring, they are termed as cycloalkanes. Unsaturated hydrocarbons contain carbon-carbon multiple bonds – double bonds, triple bonds or both. Aromatic hydrocarbons are a special type of cyclic compounds.

Alkanes

These are the saturated chains of hydrocarbons containing carbon-carbon single bonds. Methane (CH4), is the first member of this family containing single carbon atom. Since it is found in coal mines and marshy areas, is also known as ‘marsh gas’. These hydrocarbons exhibited low reactivity or no reactivity under normal conditions with acids, bases and other reagents, they were earlier known as paraffins. The general formula for alkane is CnH2n + 2, where n stands for number of hydrogen atoms in the molecule.

(A). Nomenclature

For nomenclature of alkanes in IUPAC system, the longest chain of carbon atoms containing the single bond is selected. Numbering of the chain is done from the one end so that maximum carbon will be included in chain. The suffix ‘ane’ is used for alkanes. The first member of the alkane series is CH4 known as methylene (common name) or methene (IUPAC name). IUPAC names of a few members of alkenes are given below :

| S.No. | Structure | IUPAC Name |

| 1. | CH4 | Methane |

| 2. | C2H6 | Ethane |

| 3. | C3H8 | Propane |

| 4. | C4H10 | Butane |

| 5. | C5H12 | Pentane |

| 6. | C6H14 | Hexane |

| 7. | C7H16 | Heptane |

| 8. | C8H18 | Octane |

| 9. | C9H20 | Nonane |

| 10. | C10H22 | Decane |

(B). Preparation of Alkanes

Though petroleum and natural gas are the main sources of alkanes, it can be prepared by several other methods as well.

1. From unsaturated hydrocarbons

The addition of dihydrogen to unsaturated hydrocarbons like alkenes and alkynes in the presence of a suitable catalyst under a given set of conditions produces saturated hydrocarbons or alkanes. This process of addition of dihydrogen is known as hydrogenation process.

CH2=CH2 + H2 ⟶ CH3-CH3

CH☰CH + 2H2 ⟶ CH3-CH3

2. From alkyl halides

(a) Reduction: Alkyl halides undergo reduction with zinc and dilute hydrochloric acid to give alkanes. In general the reaction can be represented as

CH3-Cl ⟶ CH4

(b) Wurtz reaction: Alkyl halides on treatment with sodium metal in dry ether give higher alkanes. This reaction is known as Wurtz reaction.

CH3Br + 2Na + BrCH3 ⟶ CH3-CH3 + 2NaBr

3. From carboxylic acids

(a) By decarboxylation of carboxylic acids: Sodium salts of carboxylic acids on heating with soda lime give alkanes containing one carbon atom less than the carboxylic acid. A molecule of carbon dioxide is eliminated which dissolves in NaOH to form sodium carbonate.

CH3COONa + NaOH ⟶ CH4 + Na2CO3

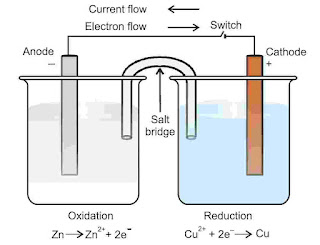

(b) Kolbe’s electrolytic method: An aqueous solution of sodium or potassium salt of a carboxylic acid on electrolysis gives alkane containing even number of carbon atoms at anode.

CH3COONa + 2H2O ⟶ CH3-CH3 + 2CO2 + H2 + NaOH

(C). Properties of Alkanes

I. Physical Properties

(i) State: Due to the weak van der Waals forces, the first four members C1 to C4 i.e., methane, ethane, propane and butane are gases. From C5 to C17 are liquids and those containing 18 carbon atoms or more are solids at 298 K. They all are colourless and odourless.

(ii) Solubility: Alkanes are generally insoluble in water or in polar solvents but they are soluble in non-polar solvents like, ether, benzene, carbontetrachloride etc. The solubility of alkanes follow the property “Like Dissolves like”.

(iii) Boiling point: The boiling points of straight chain alkanes increase regularly with the increase of number of carbon atoms. This is due to the fact that the intermolecular van der Waals forces increase with increase in the molecular size or the surface area of the molecule.

II. Chemical Properties

Generally alkanes show inertness or low reactivity towards acids, bases, oxidizing and reducing agents at ordinary conditions because of their non-polar nature and absence of π bond. The C–C and C–H bonds are strong sigma bonds which do not break under ordinary conditions but they undergo certain reactions under given suitable conditions.

(1) Halogenation reaction: When hydrogen atom of an alkane is replaced by a halogen, it is known as halogenation reaction. Halogenation takes place either at high temperature (300–500°C) or in the presence of diffused sunlight or ultraviolet light.

CH4 + Cl2 ⟶ CH3Cl + HCl

(2) Combustion: Alkanes on heating in presence of air gets completely oxidized to carbon dioxide and water. It burns with a non-luminous flame. The combustion of alkanes is an exothermic process i.e., it produces a large amount of heat.

CH4 + 2O2 ⟶ CO2 + 2H2O

(3) Controlled oxidation: When methane and dioxygen compressed at 100 atm are passed through heated copper tube at 523 K yield methanol.

2CH4 + O2 ⟶ 2CH3OH

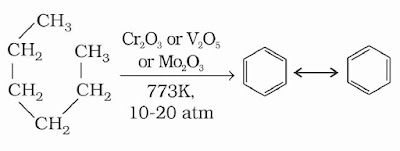

(4) Aromatization: The conversion of aliphatic compounds into aromatic compounds is known as aromatisation. n-Alkanes having six or more carbon atoms on heating to 773 K at 10–20 atmospheric pressure in the presence of oxides of vanadium, molybdenum or chromium supported over alumina get dehydrogenated and cyclised to benzene and its homologues. This reaction is also known as reforming.

(5) Reaction with steam: Methane reacts with steam at 1273 K in the presence of nickel catalyst to form carbon monoxide and dihydrogen. This method is used for industrial preparation of dihydrogen gas.

CH4 + H2O ⟶ CO + 3H2

Alkenes

Alkenes are unsaturated hydrocarbons containing at least one carbon-carbon double bond with general formula CnH2n. Alkenes are also known as olefins (oil forming) since the first member, ethylene or ethene (C2H4) was found to form an oily liquid on reaction with chlorine.

(A). Nomenclature

For nomenclature of alkenes in IUPAC system, the longest chain of carbon atoms containing the double bond is selected. Numbering of the chain is done from the end which is nearer to the double bond. The suffix ‘ene’ replaces ‘ane’ of alkanes. The first member of the alkene series is C2H4 known as ethylene (common name) or ethene (IUPAC name). IUPAC names of a few members of alkenes are given below :

| S.No. | Structure | IUPAC Name |

| 1. | C2H4 | Ethene |

| 2. | C3H6 | Propene |

| 3. | C4H8 | Butene |

| 4. | C5H10 | Pentene |

| 5. | C6H12 | Hexene |

| 6. | C7H14 | Heptene |

| 7. | C8H16 | Octene |

| 8. | C9H18 | Nonene |

| 9. | C10H20 | Dekene |

(B). Preparation

1. From alkynes: Alkynes undergo partial reduction with calculated amount of dihydrogen producing alkenes.

CH☰CH + H2 ⟶ CH2=CH2

2. From alkyl halides: Alkyl halides (R–X) on heating with alcoholic potash eliminates one molecule of halogen acid to form alkenes. This reaction is known as dehydrohalogenation i.e., removal of halogen acid.

CH3CH2Cl ⟶ CH2=CH2 + HCl

3. From alcohols by acidic dehydration: Alcohols on heating with concentrated sulphuric acid form alkenes with the elimination of one water molecule since a water molecule is eliminated from the alcohol molecule in the presence of an acid, this reaction is known as acidic dehydration of alcohols.

CH3CH2OH ⟶ CH2=CH2 + H2O

(C). Properties of Alkenes

I. Physical properties

- The first three members of alkenes are gases, the next fourteen are liquids and the higher ones are solids.

- Ethene is a colourless gas with a faint sweet smell. All other alkenes are colourless and odourless, insoluble in water but fairly soluble in non-polar solvents like benzene, petroleum ether.

- They show a regular increase in boiling point with increase in size i.e., every —CH2 group added increase the boiling point by 20–30 K.

II. Chemical properties

1. Addition of dihydrogen: Alkenes adds one mole of dihydrogen gas in presence of catalysts such as Ni at 200–250°C, or finely divided Pt or Pd at room temperature to give an alkane.

CH2=CH2 + H-H ⟶ CH3-CH3

2. Addition of halogens: Halogens like bromine or chlorine add up to alkene to form vicinal dihalides in presence of CCl4 as solvent. The order of reactivity of halogens is F > Cl > Br > I.

CH2=CH2 + Br-Br ⟶ Br-CH2-CH2-Br

3. Addition of hydrogen halides: Hydrogen halides (HCl, HBr, HI) add upto alkenes to form alkyl halides. The order of reactivity of hydrogen halides is HI > HBr > HCl. Like addition of halogens to alkenes, addition of hydrogen halides is an example of electrophilic addition reaction.

CH2=CH2 + H-Br ⟶ CH3-CH2-Br

Markovnikov rule: According to the rule, the negative part of the addendum (adding molecule) adds to that carbon atom of the unsymmetrical alkene which is maximum substituted or which possesses lesser number of hydrogen atoms.

CH3CH=CH2 + HBr ⟶ CH3-CH(Br)-CH3

Anti Markovnikov addition or Peroxide effect or Kharash effect: In the presence of peroxide, addition of HBr to unsymmetrical alkenes like propene takes place contrary to the Markovnikov rule. This happens only with HBr but not with HCl or HI. This reaction is known as peroxide or Kharash effect or addition reaction anti to Markovnikov rule.

CH3CH=CH2 + HBr ⟶ CH3-CH2-CH2-Br

4. Polymerisation: Polymerisation is the process where monomers combines together to form polymers. The large molecules thus obtained are called polymers. Other alkenes also undergo polymerisation.

n(CH2=CH2) ⟶ (-CH2-CH2-)n

Alkynes

Like alkenes, alkynes are also unsaturated hydrocarbons with general formula CnH2n – 2. They contain at least one triple bond between two carbon atoms. These have four H-atoms less compared to alkanes. The first stable member of alkyne series is ethyne commonly known as acetylenes.

(A). Nomenclature

In common system, alkynes are named as derivatives of acetylene. In IUPAC system, they are named as derivatives of the corresponding alkanes replacing ‘ane’ by the suffix ‘yne’. The position of the triple bond is indicated by the first triply bonded carbon. Common and IUPAC names of a few members of alkyne series are given in the table below :

| S.No. | Structure | IUPAC Name |

| 1. | C2H2 | Ethyne |

| 2. | C3H4 | Propyne |

| 3. | C4H6 | Butyne |

| 4. | C5H8 | Pentyne |

| 5. | C6H10 | Hexyne |

(B). Preparation

1. From calcium carbide: On industrial scale, ethyne is prepared by reacting calcium carbide with water. Calcium carbide is prepared by heating quick lime with coke. Quick lime can be obtained by heating limestone as shown in the following reactions :

CaCO3 ⟶ CaO + CO2

CaO + 3C ⟶ CaC2 + CO

CaC2 + 2H2O ⟶ Ca(OH)2 + C2H2

2. From vicinal dihalides: Vicinal dihalides on treatment with alcoholic potassium hydroxide undergo dehydrohalogenation. One molecule of hydrogen halide is eliminated to form alkenyl halide which on treatment with sodamide gives alkyne.

CH2(Br)-CH2(Br) + KOH ⟶ CH2=CH2 ⟶ CH☰CH

(A). Properties of Alkynes

I. Physical properties

- The first three members (acetylene, propyne and butynes) are gases, the next eight are liquids and higher ones are solids.

- All alkynes are colourless. All alkynes except ethyne which have an offensive characteristic odour, are odourless.

- Alkynes are weakly polar in nature and nearly insoluble in water. They are quite soluble in organic solvents like ethers, carbon tetrachloride and benzene.

- Their melting point, boiling point and density increase with increase in molar mass.

II. Chemical properties

(i) Addition of dihydrogen: Alkynes contain a triple bond, so they add up, two molecules of dihydrogen.

CH☰CH + H2 ⟶ CH2=CH2 ⟶ CH3-CH3

(ii) Addition of halogens: Alkynes contain a triple bond, so they add up, two molecules of halogen.

CH☰CH + Cl2 ⟶ CH(Cl)=CH(Cl) ⟶ CH(Cl)2-CH(Cl)2

(iii) Addition of hydrogen halides: Two molecules of hydrogen halides (HCl, HBr, HI) add to alkynes to form gemdihalides (in which two halogens are attached to the same carbon atom).

CH☰CH + HCl ⟶ CH2=CH(Cl)

(iv) Addition of water: Like alkanes and alkenes, alkynes are also immiscible and do not react with water. However, one molecule of water adds to alkynes on warming with mercuric sulphate and dilute sulphuric acid at 333 K to form carbonyl compounds.

CH☰CH + H2O ⟶ CH3-CHO

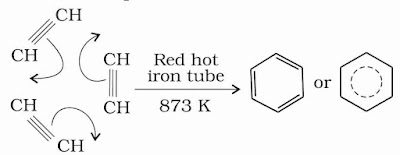

(v) Polymerisation: Ethyne on passing through red hot iron tube at 873 K undergoes cyclic polymerization. Three molecules polymerise to form benzene, which is the starting molecule for the preparation of derivatives of benzene, dyes, drugs and large number of organic compounds.

(vi) Oxidation:

2C2H2 + 5O2 ⟶ 4CO2 + 2H2O

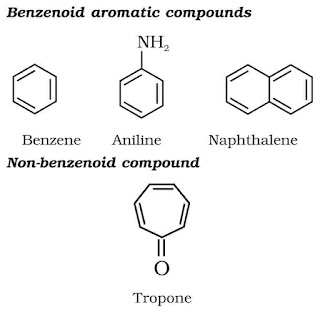

Aromatic Hydrocarbon

Aromatic hydrocarbons are also known as ‘arenes’. Since most of them possess pleasant odour (Greek; aroma meaning pleasant smelling), the class of compounds are known as ‘aromatic compounds’. Most of the compounds are found to have benzene ring. Benzene ring is highly unsaturated and in a majority of reactions of aromatic compounds, the unsaturation of benzene ring is retained. Aromatic compounds containing benzene ring are known as benzenoids and those, not containing a benzene ring are known as non-benzenoids.

Nomenclature

Since all the six hydrogen atoms in benzene are equivalent; so it forms one and only one type of monosubstituted product. When two hydrogen atoms in benzene are replaced by two similar or different monovalent atoms or groups, three different position isomers are possible which differ in the position of substituents. So we can say that disubstituted products of benzene show position isomerism. The three isomers obtained are 1, 2 or 1, 6 which is known as the ortho (o-), the 1, 3 or 1, 5 as meta (m-) and 1, 4 as para (p-) disubstitued compounds.

(B). Structure

The molecular formula of benzene, C6H6, indicates a high degree of unsaturation. All the six carbon and six hydrogen atoms of benzene are identical. On the basis of this observation August Kekule in 1865 proposed the following structure for benzene having cyclic arrangement of six carbon atoms:

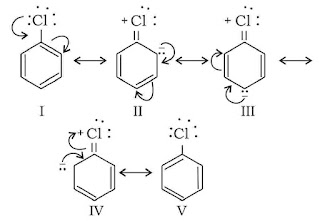

(C). Resonance

Even though the double bonds keep on changing their positions. The structures produced is such that the position of nucleus remains the same in each of the structure. The structural formula of such a compound is somewhat intermediate (hybrid) between the various propose formulae. This state is known as Resonance.

(D). Preparation of Benzene

(i) Cyclic polymerisation of ethyne: Ethyne on passing through red hot iron tube at 873 K undergoes cyclic polymerization.

(ii) Decarboxylation of aromatic acids: Sodium salt of benzoic acid i.e., sodium benzoate on heating with sodalime gives benzene.

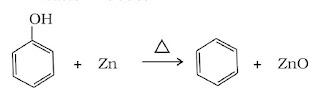

(iii) Reduction of phenol: Phenol is reduced to benzene by passing its vapour over heated zinc dust.

(E). Properties of Benzene

I. Physical Properties

- Aromatic hydrocarbons are non-polar molecules and are usually colourless liquids or solids with a characteristic aroma.

- The napthalene balls used in toilets and for preservation of clothes because of unique smell of the compound.

- Aromatic compounds are insoluble in water but soluble in organic solvents such as alcohol and ether.

- They burn with sooty flame.

II. Chemical Properties

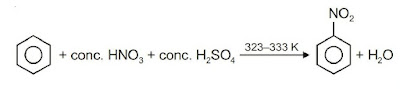

(i) Nitration: A nitro group is introduced into the benzene ring when benzene is heated with a mixture of concentrated nitric acid and concentrated sulphuric acid.

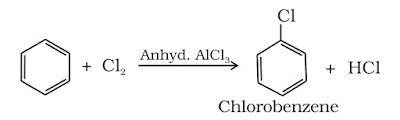

(ii) Halogenation: Arenes undergo halogenation when it is treated with halogens in presence of Lewis catalyst such as anhy. FeCl3, FeBr3 or AlCl3 to yield haloarenes.

(iii) Sulphonation: The replacement of a hydrogen atom by a sulphonic acid group in a ring is called sulphonation. It is carried out by heating benzene with fuming sulphuric acid or oleum (conc. H2SO4 + SO3).

(iv) Friedel-Crafts alkylation reaction: When benzene is treated with an alkyl halide in the presence of anhydrous aluminium chloride, alkylbenzene is formed.

Activating Groups: Electron donating groups (EDG, +M, +I, +H. C. effect) in the benzene ring will more stabilize the σ-complex (Arenium ion complex) with respect to that of benzene and hence they are known as activator.

Deactivating Groups: Electron drawing groups (–M, –I effects) will destabilize σ-complex as compared to that of benzene. Therefore substituted benzenes where substituents are electron withdrawing decreases reactivity towards SE reactions.